Research That's Pure Gold For Electronics Applications

A team of UConn researchers, partnering with engineers from United Technologies Research Center of East Hartford, has modeled and developed new classes of alloy materials for use in electronic applications that will reduce reliance on costly gold and other precious metals.

Mark Aindow and S. Pamir Alpay, professors of materials science and engineering, joined by Joseph Mantese, a UTRC Fellow, and graduate students Bilge Senturk and Yong Liu, have developed new classes of materials that behave much like gold and its counterparts when exposed to the oxidizing environments that degrade traditional base metals. Their research was funded by a grant from the U.S. Army Research Office, and the study results appeared in the Oct. 12 issue of the journal Applied Physics Letters.

With the price of gold currently hovering around $1,340 per ounce, manufacturers across the globe, including Connecticut's UTC, are scrambling for alternatives to the costly noble metals that are widely used in electronic applications, including gold, platinum, rhodium, palladium, and silver. What makes these metals attractive is their combination of excellent conductivity paired with resistance to oxidation and corrosion. Finding less costly, but equally durable and effective, alternatives is an important goal.

The team has investigated nickel, copper, and iron – inexpensive materials that may offer promise. Based on their research, they have laid out the theory and demonstrated experimentally the methodology for improving the electrical contact resistance of these base metals.

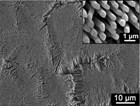

Says Aindow, "We used a combination of theoretical analysis to select the appropriate constituents, and materials engineering at the atomic level to create designer materials."

The researchers synthesized various alloys, using inexpensive base metals. Higher conductivity native oxide scales can be achieved in these alloys through one of three processes: doping to enhance carrier concentration; inducing mixed oxidation states to give electron/polaron hopping; and/or phase separation for conducting pathways.

Their work has demonstrated an improvement in contact resistance of up to one million-fold over that for pure base metals, so that base metal contacts can now be prepared with contact properties near those of pure gold.

SOURCE: University of Connecticut